R Code

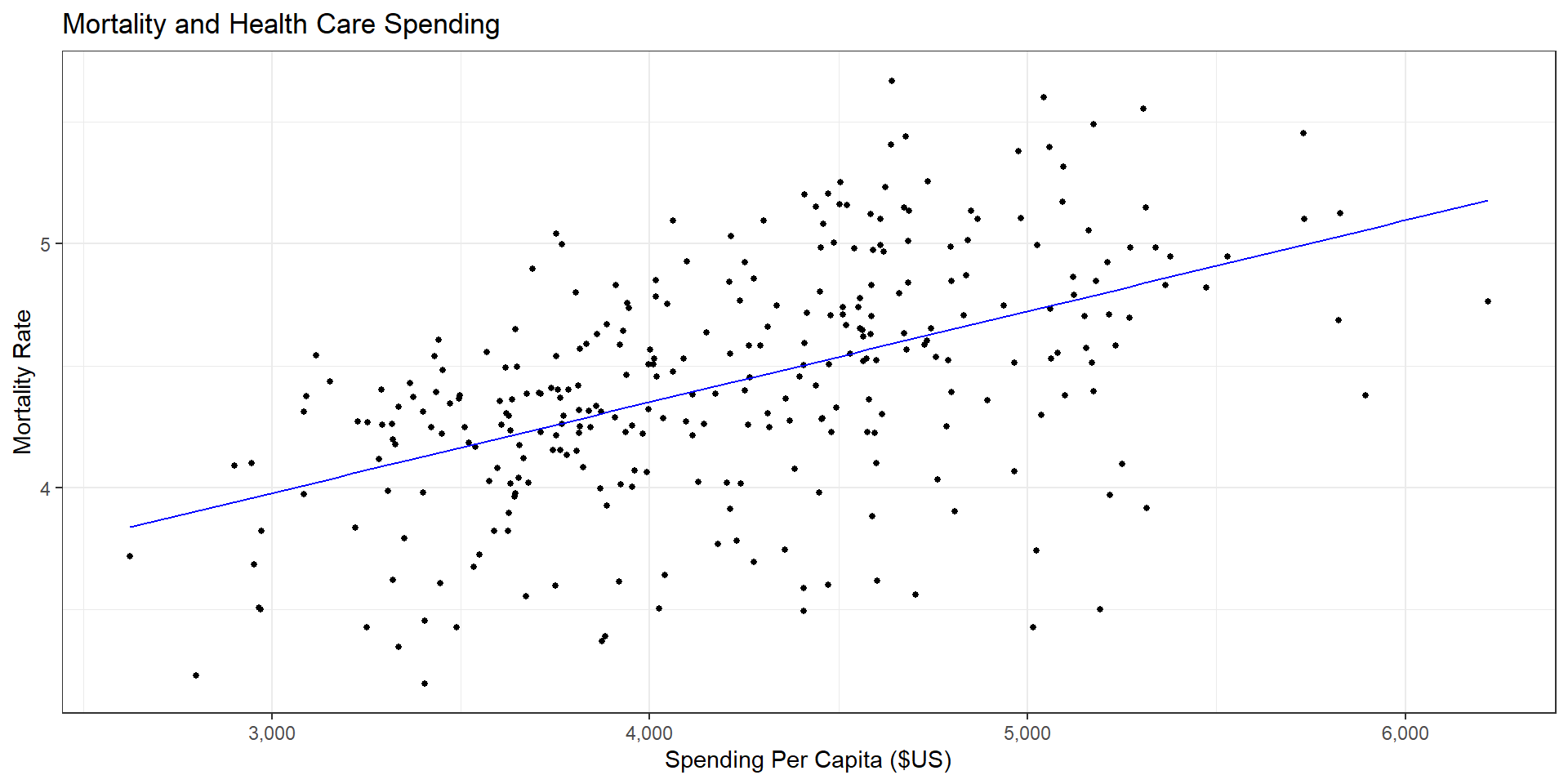

ggplot(data = (dartmouth.data %>% filter(Year==2015)),

mapping = aes(x = Expenditures, y = Total_Mortality)) +

geom_point(size = 1) + theme_bw() + scale_x_continuous(label = comma) +

geom_smooth(method="lm", se=FALSE, color="blue", size=1/2) +

labs(x = "Spending Per Capita ($US)",

y = "Mortality Rate",

title = "Mortality and Health Care Spending")