Main takeaways

Explain, using a graph, how unraveling could occur in a market with adverse selection.

Discuss and show graphically how an individual mandate or subsidies could help to alleviate or minimize the adverse selection problem.

In practice, people know more about their health than insurers. This is a form of asymmetric information.

Here’s a good example, Costs during special enrollment periods.

For any amount of unraveling, we need at least two features in the market:

Think in periods: if initially \(AC > p\), insurers incur losses and raise \(p\).

Assume the insurer’s cost function is \(C=100q - 2q^{2}\), where \(q\) denotes the number of people enrolled in the plan. Further assume that demand is given by \(D=140-4q\). Assuming the insurer enters the market with \(p_{1}=40\),

Assume that the insurer’s cost function is given by \(C=100q - 2q^{2}\), where \(q\) denotes the number of people enrolled in the plan. Further assume that the inverse demand function takes the form, \(D=110 - 3q\), and that there are 20 individuals total in this market.

So, are the exchanges in a “death spiral”?

Standard & Poor’s writes: “The ACA individual market is not in a ‘death spiral.’ However, every time something new (and potentially disruptive) is thrown into the works, it impedes the individual market’s path to stability.”

Can you examine each of these policies graphically? How do they differ from the patient’s or government’s point of view?

Based on our discussion of adverse selection and health insurance markets, what would you expect to happen if we increased the Medicare age from 65 to 70 years old?

What if individuals who are high risk are also less risk-averse? In this case, individuals who are willing to pay the most for health insurance (the most risk averse) are actually less risky and therefore the cheapest to insure. Very different policy implications (e.g., individual mandate is bad in this case).

Explain, using a graph, how unraveling could occur in a market with adverse selection.

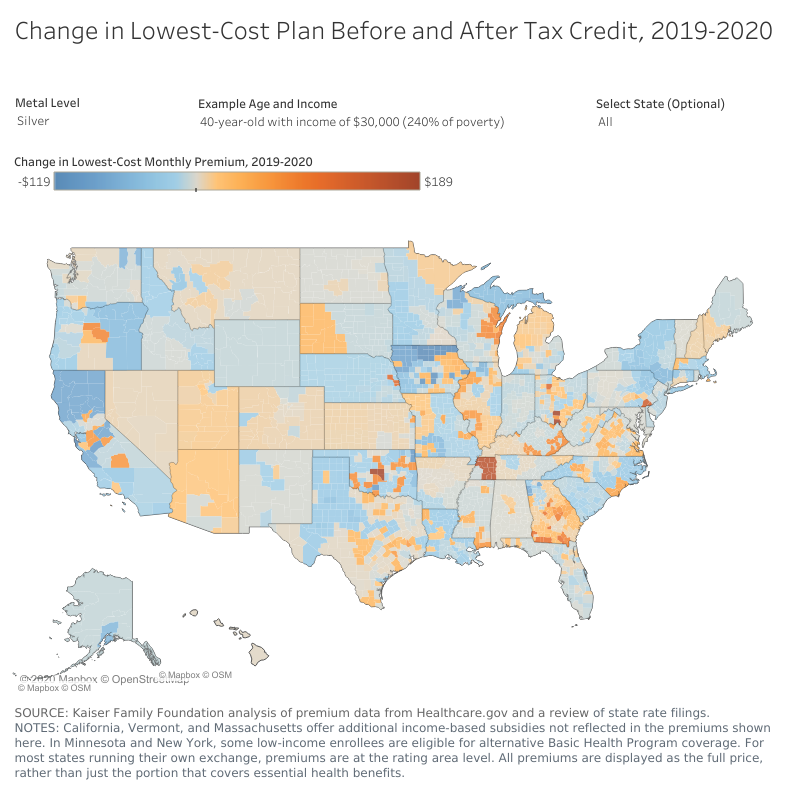

Discuss and show graphically how an individual mandate or subsidies could help to alleviate or minimize the adverse selection problem.