Regulation and Innovation

Ian McCarthy | Emory University

Outline for today

- Innovation and R&D decisions

- MEI, dynamic efficiency, and what gets researched

- Prices, competition, and high drug spending

- U.S. vs peers, brand vs generic, limited competition

- U.S. vs peers, brand vs generic, limited competition

- Policy responses and global equity

- Price regulation, push vs pull incentives, global public good

Innovation and R&D Decisions

What is innovation?

How would you define “innovation” in pharma?

- Should not just mean a new drug, but a new drug that is better than existing treatments

- Not clear this is always the argument made in the media

Inducing Innovation

- Governments often care not just about using existing technologies efficiently, but about creating new ones

- Classic example: British Parliament’s 1714 Longitude Prize, which paid for a method to determine longitude at sea

- The prize worked: it induced decades of R&D by clockmakers, eventually yielding highly accurate marine chronometers

- Question for today: what “prizes” or incentives are we implicitly setting for pharma R&D?

What governs innovation?

- Strong empirical evidence that firms internalize future profits of a drug when making R&D decisions

- Investment decision can be modeled as:

- Ranking of expected returns to potential new drugs, including costs of manufacturing, packaging, marketing, and distribution. This is the Marginal Efficiency of Investment (MEI)

- Comparison of MEI to cost of capital

- Investment in the drugs to the point where MEI=cost of capital

MEI and the Cost of Capital

- Downward-sloping MEI: diminishing returns to additional R&D projects

- Horizontal line: cost of capital

- A leftward shift of MEI (e.g., from lower prices) reduces the profit-maximizing R&D level

Dynamic Efficiency

- Policies that lower drug prices today reduce current spending but also reduce expected future profits

- If firms internalize these future profits, lower prices → lower MEI → less R&D and fewer future drugs

- Dynamic efficiency tradeoff:

- Static gain: lower prices and better access for today’s patients

- Dynamic cost: potential reduction in future innovation

- Example: debates around Medicare drug price negotiation and the Inflation Reduction Act can be viewed through this lens

What Gets Researched? Preventives vs Treatments

- Even holding total market size fixed, incentives can differ sharply between:

- Preventive products (e.g., vaccines)

- Treatments after disease onset

- Kremer & Snyder show that with heterogeneous risk, firms may earn more from treatments than preventives, even when preventives generate more social surplus

- Intuition: high-risk patients are easier to identify and treat; low-risk individuals may not buy prevention at a price that fully reflects its social value

Kremer–Snyder Stylized Example

- Suppose:

- Some consumers have a high probability of getting the disease; others have low risk

- A preventive reduces risk; a treatment cures the disease after it appears

- With the same underlying health risk and willingness-to-pay:

- Treatment can yield higher firm revenue than prevention because only high-risk consumers are willing to pay high prices for the preventive

- Takeaway: private R&D may tilt toward treatments over preventives, even when prevention is socially preferable

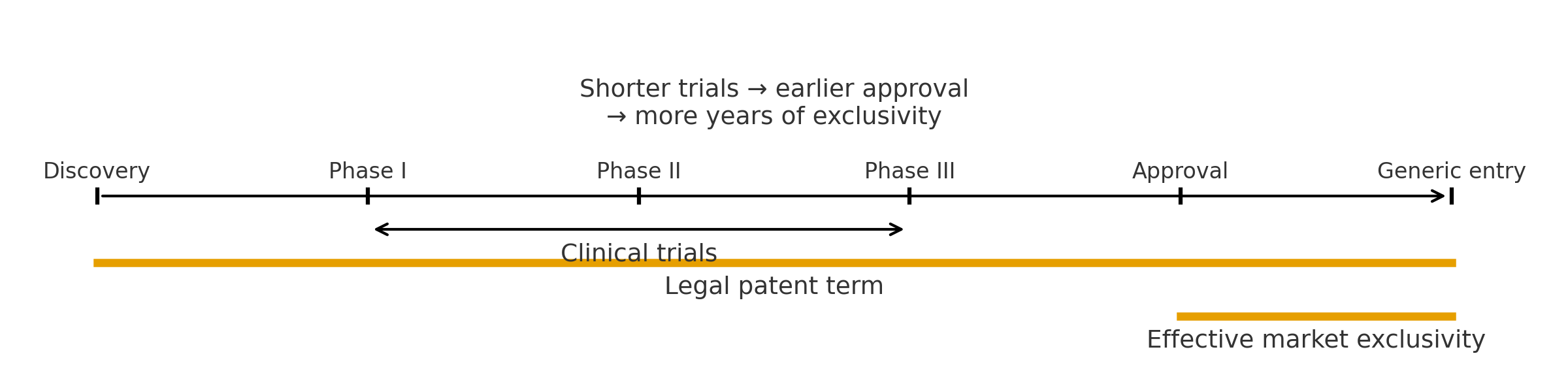

Stage of Disease and Trial Length

- Firms also choose which stage of disease to target

- Shorter clinical trials mean:

- Faster time to approval

- Longer period of effective market exclusivity

- Empirically, cancer R&D is heavily concentrated in late-stage and recurrent disease, with far fewer trials on prevention or very early-stage disease

- This suggests underinvestment in long-term, prevention-oriented projects relative to social value

Evidence: Cancer Trials by Stage

- Data on cancer clinical trials show:

- Very high numbers of trials for recurrent and metastatic disease

- Much smaller numbers for in situ cancers and especially for prevention trials

- Interpretation:

- Market incentives favor drugs with shorter, cheaper trials and quicker payoffs

- Long-horizon prevention may be dynamically underprovided

Prices, Competition, and High Drug Spending

Paper Discussion 1

The High Cost of Prescription Drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform

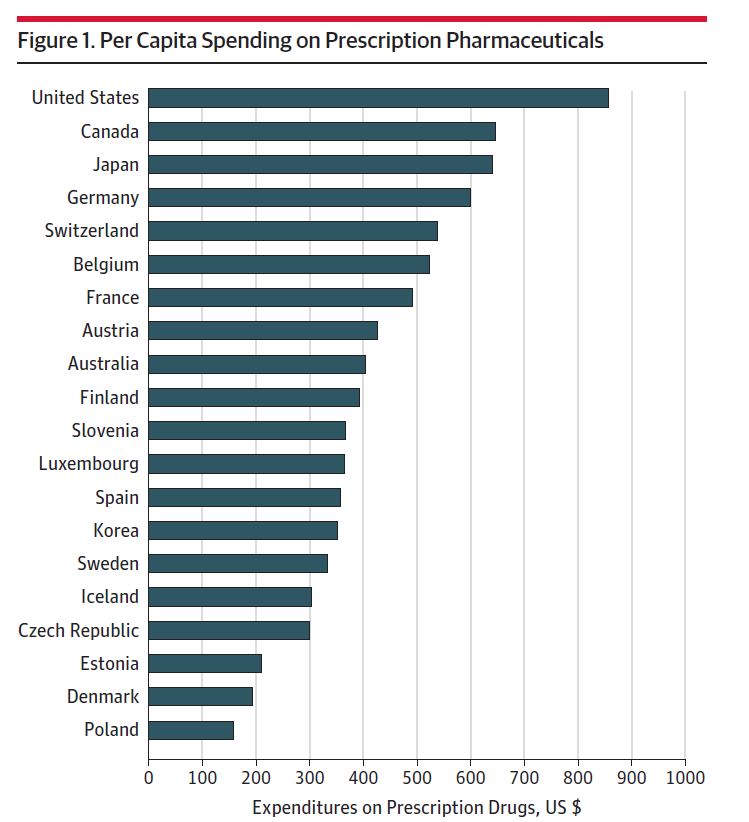

1. High Spending

- Higher spending in the U.S. compared to peer countries

- Faster spending growth in the U.S. compared to peer countries

But…

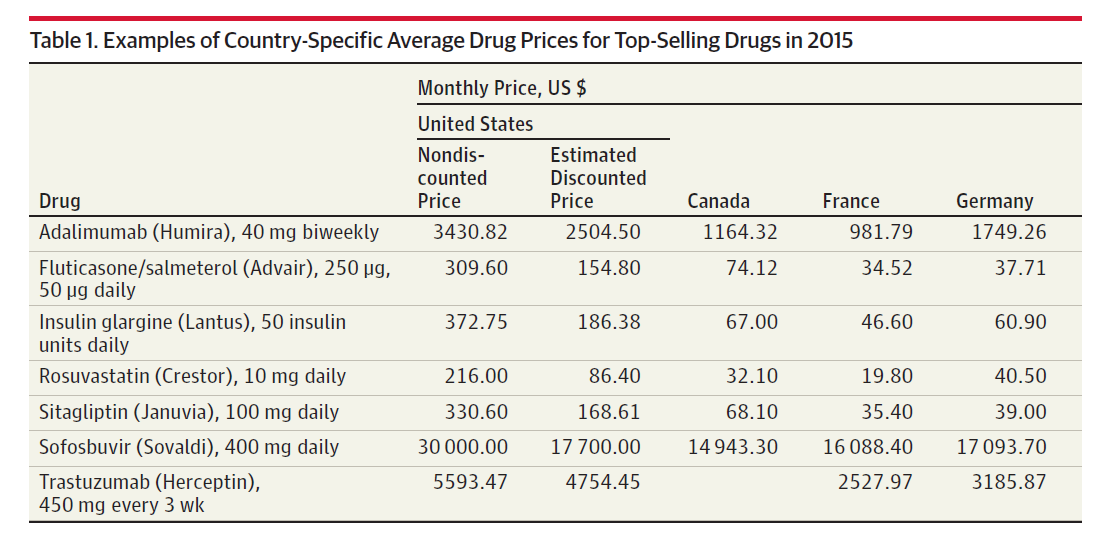

- Spending on even very high cost drugs can still be cost-effective

- Sovaldi (hepatitis C) found to be cost-effective despite $84,000 per 12-week course

Research Questions

- What factors seem to contribute to pharma price increases?

- What policies can help ensure prices match value and that drugs are available in an equitable way?

Brand name vs generic

- Annual cost of highly specialized brand name drugs exceeds $250,000 per patient!

- High brand-name prices now extend to drugs with some substitutes (not just rare conditions)

- Generic drugs generally lower priced, but some examples of high price increases

- Daraprim, 63-year old treatment for toxoplasmosis, increases 5500% (from $13.50 to $750) in 2015

- A few hundred generic drugs experienced price increases of more than 1000% from 2008 to 2015

- Why? Monopoly products, despite no patent protection

Why such high prices?

- Prices set by manufacturers, PBMs, insurers, and pharmacies

- Little direct price regulation

- Conversely, the UK specifically requires cost-effectiveness thresholds before allowing coverage

Case Study: Avastin and Price Discrimination

- Avastin was approved for certain cancers and priced accordingly

- Physicians later discovered that very small doses were also effective for treating macular degeneration

- At the cancer price, the implied price per eye injection for ophthalmology was extremely high

- Regulatory and reimbursement rules limited Genentech’s ability to charge very different prices across indications, creating tensions around off-label use and follow-on products

- Example of how indication, dosing, and pricing regulations interact with firms’ incentives

Drug Life Cycle and Patent Clock

- Legal patent term starts before approval; effective market exclusivity is shorter

- Shorter clinical trials bring approval earlier and lengthen effective exclusivity

- R&D incentives are shaped by where projects sit on this timeline

Competition

- Patent protection usually lasts around 20 years (starts before drug is officially approved)

- Companies can apply for extended patent protection for 5 years (max of 14 years in the market)

- Additional 6 months if testing products in children

- On average, 12.5 years of post-market exclusivity for widely used drugs and 14.5 years for highly innovative drugs (first-in-class)

Limited competition even for brand name drugs with some substitutes. Why?

- Fragmentation

- Information problems

- Physician agency

Firms can also deter generic entry, via:

- Additional patents on coating, method of administration, etc.

- Example: Nexium is derivative of Prilosec (omeprazole), sold for 600% markup over generic omeprazole

- Significant settlements to generic drug companies

- Delays in approval for generic drugs (FDA delays of 3-4 years, now closer to 1-2 years)

Barriers to substituting brand name drugs with generic drugs even after generic entry:

- Drug product selection laws in 30 states that allow but do not require pharmacists to substitute generics

- 26 states that require patient consent when replacing brand name with generic drugs

- All states allow “dispense-as-written”, which restricts pharmacists’ ability to substitute brand name drugs

Drug Pricing Supply Chain

- Already discussed…

- Manufacturers set list prices and negotiate rebates with PBMs

- Insurers reimburse pharmacies; patients face cost sharing at the pharmacy

- PBM payment structures can weaken incentives to push aggressively for lower net prices

Other barriers to competition among generics and brand name:

- PBMs often paid based on insurer spending on specific drugs, therefore little incentive to intensely negotiate prices

- From US House Committee on Oversight and Government reform:

“The investigation revealed, for example, that Turing received ‘no pushback from payors’ when it increased ‘Chenodal price 5x… [Thiola] price 21x… [and Daraprim] price 43x.’

Justification for high prices

Industry argument that significant R&D costs necessitate higher prices

But…

- Half of the “most transformative drugs” developed (or started) in academic centers

- Many drugs also started in small companies later acquired by larger manufacturer

- “Innovation” means more than just another drug

- Current price growth simply not sustainable

Policy Responses and Global Equity

Price regulation and innovation

- Price regulation (reference pricing, direct price caps, etc.)

- In general, lower prices discourages innovation by shifting MEI inward

- How much? Some estimates of price elasticity of R&D at 0.6

- 10% price cut reduces R&D by 6%

- But what innovations are “lost”? Hard to say

How to influence innovation?

- If firms are maximizing profits, then the only way to influence innovation is to change the MEI or the cost of capital

- Shift MEI outward via:

- Changing marketing regulations (DTC advertising)

- Increasing demand for a drug (market exclusivity, coverage under public insurance)

- Shift cost of capital down via:

- Easier access to funding (tax credits, grants, etc.)

How to influence innovation?

- Which approach is “best”?

- Politically, these are NOT identical policies

- Pull incentives require no up-front costs

- Pull incentives tend to place R&D burden onto pharma customers

- Push incentives require up-front government investment

- Push incentives place burden on taxpayers

What can we do?

Federal Policies:

- Limit secondary patents for minor changes

- Combat anticompetitive practices like pay-for-delay

- Allow negotiation of prices and formulary exclusions by Medicare

- Faster time to market for generics

State Policies:

- Drug product selection laws

- Allow negotiation of prices and formulary exclusions by Medicaid

Advanced Market Commitments (AMCs)

- Governments or donors commit in advance to buy a specified quantity of a vaccine or drug at a pre-set price

- Goal: create a credible, profitable market for products that primarily benefit low-income countries

- Example: AMC for pneumococcal vaccines in low-income countries

- AMCs act like:

- A pull incentive (payment conditional on success)

- Targeted at areas where standard patent-based returns would be too low

Patent Buyouts and Delinking

- Patent buyouts:

- Government buys the patent at an auction-based price plus a markup

- Drug is then placed in the public domain (generic competition; low prices)

- Broader “delinkage” proposals:

- Replace or reduce reliance on monopoly pricing

- Reward firms through prizes or lump-sum payments tied to clinical and social value

- These ideas aim to preserve dynamic incentives for R&D while reducing static monopoly distortions in prices

Paper Discussion 2

Who Pays for Pharma R&D?

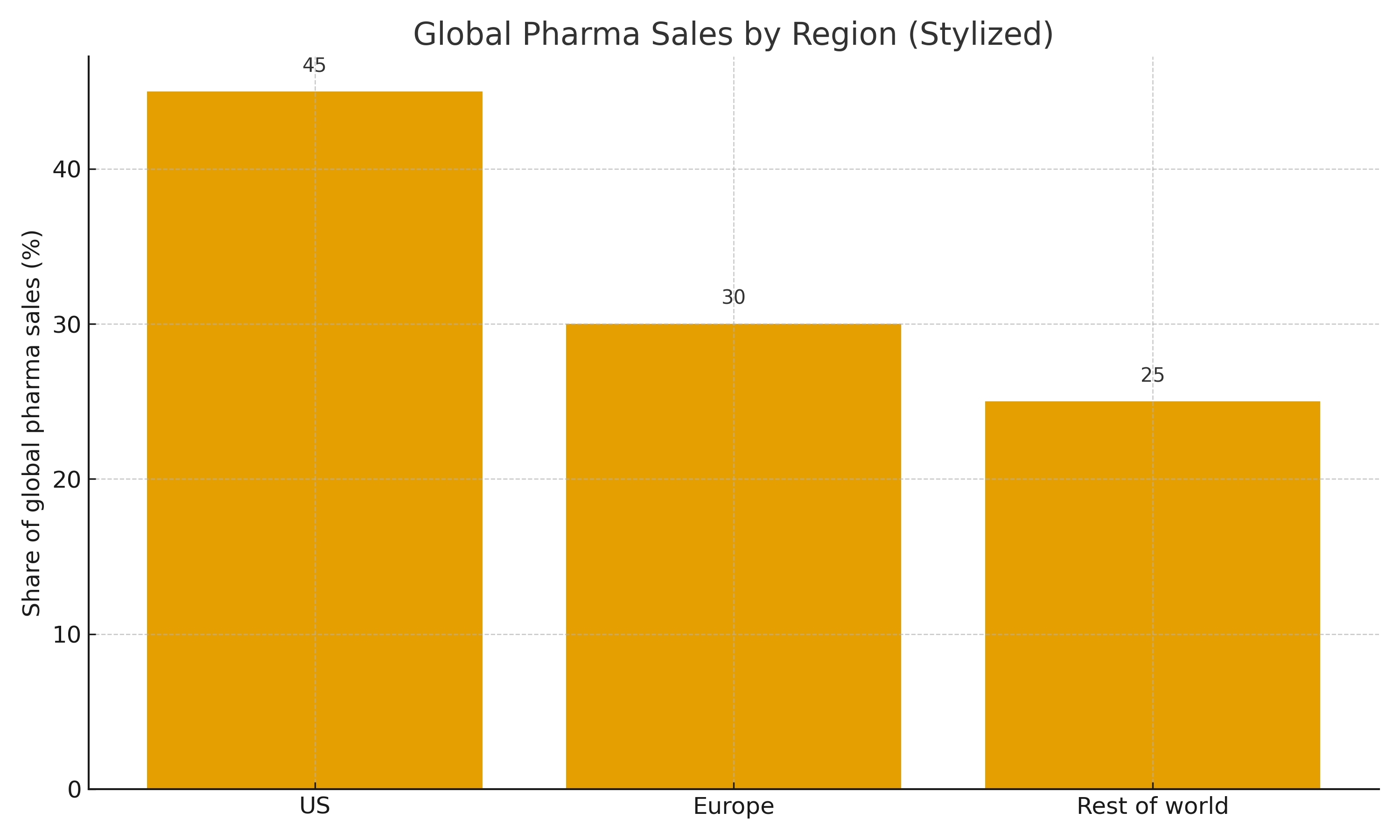

- The U.S. accounts for a disproportionate share of global pharmaceutical sales (stylized)

- Other high-income regions also contribute, but to a lesser extent

- Sets up the question of whether the U.S. is over-contributing to global R&D incentives

US Subsidizing ROW

- US clearly pays higher prices than other countries

- Strong evidence that US contribution to profit for future innovation is higher than it should be

- That said, the ROW contribution is meaningful (all other countries do not force prices to marginal costs)

- Authors urge a more international view of spending, suggesting better policy is to advocate for higher prices elsewhere rather than directly for lower prices in the US

Pulling It Together: Designing R&D Incentives

- Standard patent system: strong dynamic incentives but high prices and uneven R&D portfolio

- Distortions:

- Treatments vs preventives

- Short- vs long-horizon projects

- Diseases of rich vs poor countries

- Policy menu:

- Adjust prices and coverage (Medicare/Medicaid negotiations, global pricing)

- Add targeted push and pull incentives (NIH funding, AMCs, prizes, buyouts)

- Open question: what mix best balances current access, future innovation, and global equity?